Dr. Simon J. Greenhill

I study language and cultural evolution, focusing on why and how humans created the remarkable diversity of languages we see today and what they reveal about our shared human prehistory.

Using Bayesian phylogenetic methods, I explore questions such as how the Austronesian peoples navigated and settled the Pacific and how linguistic structures evolve and co-adapt over time. To support this work, I’ve developed large-scale databases that help uncover the patterns and processes driving the evolution of language and culture, offering deeper insights into the story of humanity.

You can find me on Bsky, Github, or for real at the University of Auckland.

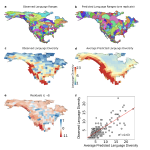

Demographic shifts, inter-group contact, and environmental conditions drive language extinction and diversification.

Pacheco Coelho MT, Haynie HJ, Bowern C, Coelho RK, Greenhill SJ, Kirby KR, Rangel TF, Gavin MC. 2026. Demographic shifts, inter-group contact, and environmental conditions drive language extinction and diversification. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 293: 20242361.

Humans currently collectively use thousands of languages. The number of languages in a given region (i.e. language 'richness') varies widely. Understanding the processes of diversification and homogenization that produce these patterns has been a fundamental aim of linguistics and anthropology. Empirical research to date has identified various social, environmental, geographic, and demographic factors associated with language richness3. However, our understanding of causal mechanisms and variation in their effects over space has been limited by prior analyses focusing on correlation and …

Abstract PDF 10.1098/rspb.2024.2361Three evolutionary radiations shaped the evolution of global religious diversity..

Ejova A, Sheehan O, Bouckaert R, Greenhill SJ, Krátký J, Kotherová S, Cigán J, Kundtová Klocová E, Kundt R, Watts J, Bulbulia J, Atkinson QD & Gray RD. 2025. Three evolutionary radiations shaped the evolution of global religious diversity. Evolutionary Human Sciences, 7.

Religious diversity has had profound consequences in human history, but the dynamics of how it evolves remain unclear. One unresolved question is the extent to which religious denominations accumulate gradually or are generated in rapid bursts associated with specific historical events. Anecdotal evidence tends to favour the second view, but quantitative evidence on a global scale is lacking. Phylogenetic methods that treat religious denominations as evolving lineages can help to resolve this question. Here we apply computational phylogenetic methods to a purpose-built data set documenting 291 …

Abstract PDF 10.1017/ehs.2025.10027Enduring constraints on grammar revealed by Bayesian spatiophylogenetic analyses..

Verkerk A, Shcherbakova O, Haynie HJ, Skirgård H, Rzymski C, Atkinson QD, Greenhill SJ & Gray RD. 2025. Enduring constraints on grammar revealed by Bayesian spatiophylogenetic analyses. Nature Human Behaviour.

Human languages show astonishing variety, yet their diversity is constrained by recurring patterns. Linguists have long argued over the extent and causes of these grammatical ‘universals’. Using Grambank—a comprehensive database of grammatical features across the world’s languages—we tested 191 proposed universals with Bayesian analyses that account for both genealogical descent and geographical proximity. We find statistical support for about a third of the proposed linguistic universals. The majority of these concern word order and hierarchical universals: two types that have featured …

Abstract PDF 10.1038/s41562-025-02325-zA solid base for scaling up: the structure of numeration systems..

Pelland J-C, Greenhill SJ, Walworth M, & Bender A. 2025. A solid base for scaling up: the structure of numeration systems. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 380: 1937.

While numeration systems are found in almost every human society, they also vary strikingly around the globe. One important feature of many systems is being structured around a base. The presence, format and size of a base have implications for how representations of numbers are composed, conceptualized and used. The numerical cognition literature is rife with claims about which bases prevail, with sweeping generalizations on their origins and evolution. Yet these claims are rarely scrutinized, and research on numeration systems is plagued by a surprising lack of consensus on what a base is. …

Abstract PDF 10.1098/rstb.2024.0207

Projects:

Languages of Barrier Islands, Sumatra - Description, History and Typology

The Barrier Islands Languages project is a project funded by the Australian Research Council Discovery Project grant (DP230102019) titled: “Languages of Barrier Islands, Sumatra: Description, History and Typology”.

This project will run between 2023 and 2027 and investigate under-/undocumented Austronesian languages of the Barrier Islands, including Mentawai, (Simaluaya) Nias, Semeulue and Sikule, as well as neighbouring Northwest Sumatra languages, such as Simalungun Batak. New knowledge will be generated into the languages, cultures and societies of the region and be made freely available to the public.

Research will uncover past migration patterns in Southeast Asia, advance language theory, such as linguistic typology and language change, and support the computational modelling of Austronesian for future language technologies.

Grambank - a database of structural (typological) features of language

Grambank is a database of structural (typological) features of language. It consists of 195 logically independent features (most of them binary) spanning all subdomains of morphosyntax. The Grambank feature questionnaire has been filled in, based on reference grammars, for 2,467 languages. The aim is to eventually reach as many as 3,500 languages. The database can be used to investigate deep language prehistory, the geographical-distribution of features, language universals and the functional interaction of structural features.

Kinbank - Database of Kinship terminology

Kinbank is a database of kinship terminologies to be used for exploring cross-linguistic diversity in kinship organisation. The database includes 1229 languages and a set of 100 core kin types between Grandparents and Grandchildren, and between Parent’s siblings, and Parent’s siblings’ children. A major advantage of Kinbank is the focused language family sampling and sampling based on occurrence in existing anthropological databases (e.g. d-place.org), allowing us to test the relationship between languages and behaviour. This allows the use of phylogenetic methods to reconstruct the states of proto-kinship, account for common ancestry in models of kinship change, and test for correlated evolution between linguistic and behavioural patterns.

Lexibank - a public repository of standardized wordlists with computed phonological and lexical features

The past decades have seen substantial growth in digital data on the world’s languages. At the same time, the demand for cross-linguistic datasets has been increasing, as witnessed by numerous studies devoted to diverse questions on human prehistory, cultural evolution, and human cognition. Unfortunately, most published datasets lack standardization which makes their comparison difficult. Here, we present a new approach to increase the comparability of cross-linguistic lexical data. We have designed workflows for the computer-assisted lifting of datasets to Cross-Linguistic Data Formats, a collection of standards that make these datasets more Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR). We test the Lexibank workflow on 100 lexical datasets from which we derive an aggregated database of wordlists in unified phonetic transcriptions covering more than 2000 language varieties. We illustrate the benefits of our approach by showing how phonological and lexical features can be automatically inferred, complementing and expanding existing cross-linguistic datasets.

GELATO - GEnes and LAnguages TOgether

The GeLaTo dataset is a worldwide diversity panel of available population genetic samples matched with databases of linguistic, cultural and environmental diversity. Population genetic samples are assigned to existing GlottoCodes, following ethnolinguistic criteria: the data is filtered following the indication of geneticists, linguists, cultural anthropologists and historians. The dataset provides elaborated summary statistics such as genetic diversity within a population, genetic proximity between pairs of populations, sharing of identical motifs, and demographic history reconstructions.

CLICS3 - Database of Cross-Linguistic Colexifications

The original Database of Cross-Linguistic Colexifications (CLICS), has established a computer-assisted framework for the interactive representation of cross-linguistic colexification patterns. It has proven to be a useful tool for various kinds of investigation into cross-linguistic semantic associations, ranging from studies on semantic change, patterns of conceptualization, and linguistic paleontology. But CLICS has also been criticized for obvious shortcomings. Building on standardization efforts reflected in the CLDF initiative and novel approaches for fast, efficient, and reliable data aggregation, CLICS² expanded the original CLICS database. CLICS³ - the third installment of CLICS - exploits the framework pioneered in CLICS² to more than double the amount of data aggregated in the database.