Societies of strangers do not speak grammatically simpler languages

Authors:

Citation:

Details:

Published: 8 August, 2023.

Download:

Abstract:

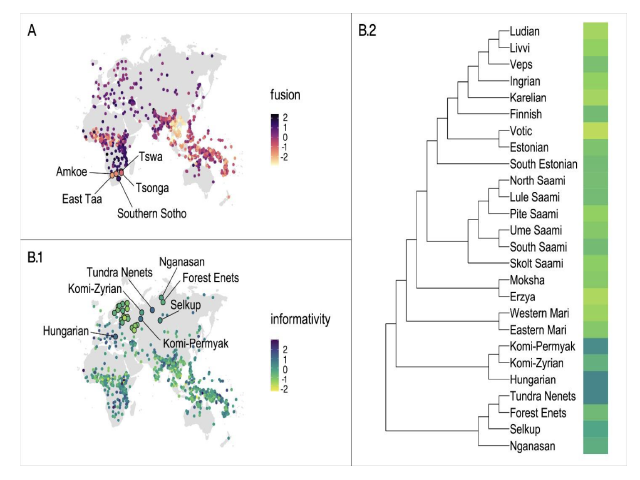

Many recent proposals claim that languages adapt to their environments. The linguistic niche hypothesis claims that languages with numerous native speakers and substantial proportions of nonnative speakers (societies of strangers) tend to lose grammatical distinctions. In contrast, languages in small, isolated communities should maintain or expand their grammatical markers. Here, we test these claims using a global dataset of grammatical structures, Grambank. We model the impact of the number of native speakers, the proportion of nonnative speakers, the number of linguistic neighbors, and the status of a language on grammatical complexity while controlling for spatial and phylogenetic autocorrelation. We deconstruct ‘grammatical complexity’ into two separate dimensions: how much morphology a language has (‘fusion’) and the amount of information obligatorily encoded in the grammar (‘informativity’). We find several instances of weak positive associations but no inverse correlations between grammatical complexity and sociodemographic factors. Our findings cast doubt on the widespread claim that grammatical complexity is shaped by the sociolinguistic environment.